Patrick Ewing

Patrick Aloysius Ewing Sr. (born August 5, 1962) is a Jamaican-American basketball coach and former professional player who is a basketball ambassador for the New York Knicks of the National Basketball Association (NBA) where he played most of his career as the starting center before ending his playing career with brief stints with the Seattle SuperSonics and Orlando Magic. Ewing is regarded as one of the greatest centers of all time, playing a dominant role in the New York Knicks' 1990s success.[1]

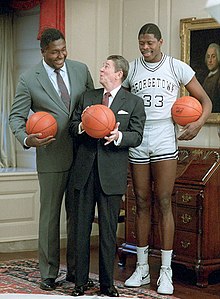

Highly recruited out of Cambridge, Massachusetts,[2] Ewing played center for Georgetown for four years—in three of which the team reached the NCAA championship game. ESPN in 2008 designated him the 16th-greatest college basketball player of all time.[3] He had a seventeen-year NBA career, predominantly playing for the New York Knicks, where he was an eleven-time all-star and named to seven All-NBA teams. The Knicks appeared in the NBA Finals twice (1994 and 1999) during his tenure. He won Olympic gold medals as a member of the 1984 and 1992 United States men's Olympic basketball teams.[4] Ewing was selected as one of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History in 1996 and as one of the 75 Greatest Players in NBA History in 2021.[5][6] He is a two-time inductee into the Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield, Massachusetts (in 2008 for his individual career and in 2010 as a member of the 1992 Olympic team).[7] Additionally he was inducted into the U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame as a member of the "Dream Team" in 2009. His number 33 was retired by the Knicks in 2003.

Early life

[edit]Ewing was born August 5, 1962, in Kingston, Jamaica to Carl and Dorothy Ewing. He was born one day before Jamaica declared independence.[8] As a child, he excelled at cricket and soccer. In 1975, Ewing moved to the United States and settled with his family outside Boston in Cambridge, Massachusetts.[9]

Ewing learned to play basketball at Cambridge Rindge and Latin School with the help of John Fountain and his coach Mike Jarvis. With only a few years of playing experience, Ewing developed into one of the best high school players in the country, and among the most intimidating forces ever seen at the level given his size and athleticism. Due to his stature and the team's dominance, Ewing was subject to taunts and jeers from hostile away crowds. Once rival fans even rocked the team bus when Ewing's squad arrived to play an away game.[10] Ewing led Cambridge Rindge and Latin to three consecutive Massachusetts Div. I state championships from 1979 to 1981.[11] In order to prepare for college, Ewing joined the MIT-Wellesley Upward Bound Program.

College career

[edit]As a senior in high school, Ewing signed a letter of intent to play for coach John Thompson at Georgetown University. Ewing made his announcement in Boston, in a room full of fans who were hoping for him to play for local schools Boston College or Boston University; when Ewing announced his decision to play at Georgetown, the fans left the room. During his recruitment, Ewing was very close to signing a letter of intent to play for Dean Smith and the University of North Carolina; however, while on his recruiting visit, he witnessed a nearby rally for the Ku Klux Klan, which dissuaded him from going there.[12] Ewing made six recruiting visits in all; he also visited UCLA and Villanova.[13]

As a freshman during the 1981–82 season, Ewing became one of the first college players to start and star on the varsity team as a freshman. That year, Ewing led the Hoyas to their second Big East tournament title in school history and a #1 seed in the NCAA Tournament. In the tournament, the Hoyas advanced to their first Final Four since 1943, where they defeated the University of Louisville, 50–46, to set up a showdown in the NCAA Final against North Carolina. In one of the most star-studded championship games in NCAA history, Ewing was called for goaltending five times in the first half (later revealed to be intentional at the behest of coach John Thompson), setting the tone for the Hoyas and making his presence felt. The Hoyas led late in the game, but a shot by future NBA superstar Michael Jordan gave North Carolina the lead. Georgetown still had a chance at winning the game in the final seconds, but Freddy Brown mistakenly threw a bad pass directly to opposing player James Worthy, sealing the win for the Tar Heels.

For the 1982–83 season, Ewing and the Hoyas began the season as the second-seeded ranked team in the country. An early-season showdown with #1 ranked Virginia and their star center Ralph Sampson was dubbed the "Game of the Decade". Virginia's veteran team won, 68–63, but Ewing at one point slam-dunked right over Sampson, a play which established Ewing as a dominating "big man".[14][15] The Hoyas posted a 22–10 record for the season and made another NCAA Tournament appearance, but Georgetown was defeated in the second round of the tournament by Memphis State. This would be the only season in Ewing's Georgetown career where they did not make it at least as far as the National Championship game.

In the 1983–84 season, Ewing led Georgetown to the Big East regular-season championship, the Big East tournament championship and another #1 seed in the NCAA Tournament. Also, he was named the Big East Player of the Year. The Hoyas ultimately advanced to the Final Four for the third time in school history (and second time with Ewing) to face Kentucky, a team which had never lost a national semifinal game and was led by the "Twin Towers", Sam Bowie and Melvin Turpin. Georgetown was able to turn an early 12 point deficit into a 53–40 win to advance to the National Championship game.[16] In the final, the Hoyas faced the University of Houston, led by future Hall of Fame center Hakeem Olajuwon. Ewing and Georgetown prevailed with an 84–75 victory, giving the school its first and only NCAA Championship in school history. Ewing was named the tournament's Most Outstanding Player.

For the 1984–85 season, Ewing's senior year, Georgetown was ranked #1 in the nation for the majority of the campaign. Ewing was again named the Big East Player of the Year and the team won the Big East tournament title yet again. They entered the NCAA tournament as the #1 overall seed of the East Region, where they wound up advancing to another Final Four, their third in four years. In the National Semifinal game, Georgetown faced their Big East rivals, St. John's and Chris Mullin, the fourth meeting between the schools that year. The Hoyas easily defeated the Redmen 77–59, setting up a matchup with another Big East rival in unranked Villanova for the title. An overwhelming favorite going into the game, Georgetown was upset by the Wildcats 66–64, who shot a record 78.6 percent (22 of 28) from the floor, denying Ewing and Georgetown back-to-back titles. At the conclusion of the season, Ewing was awarded the Naismith Player of the Year Award and the Associated Press Player of the Year.

Ewing's four-year college career is cited as one of the most successful college runs of all time. Among his many accomplishments, he helped Georgetown reach the final game of the NCAA Tournament three out of four years, win three Big East tournament titles, four Big East Defensive Player of the Year awards and was named a first-team All-American three times. He also left a cultural impact on the sport in a variety of ways. He was one of the first freshmen to not only start for but lead a major college basketball team, something unheard of back in his era. Also, he developed a habit of wearing a short-sleeved T-shirt underneath his jersey, which started a fashion trend among young athletes that lasts to this day.

NBA career

[edit]New York Knicks (1985–2000)

[edit]

We've had the Mikan era, the Russell era, the Kareem era ... now we'll have the Ewing era.

— Pat O'Brien, quoting an unnamed NBA scouting director just before the 1985 NBA draft lottery.[17]

Ewing was expected to be the top pick in the 1985 NBA draft. The team that selected him would be making history by doing so. From 1966 until 1984, the NBA draft was conducted similarly to the NFL draft, where teams are awarded draft positions based on winning percentage. The difference was that instead of the team with the lowest percentage automatically being awarded the top pick, the NBA held a coin toss between the teams with the worst records in each conference and the winner of the coin toss selected first with the loser automatically picking second. This practice tended to encourage teams to purposely lose games in order to improve their draft position and potentially get into the coin toss. The only way two teams from the same conference could have the first two picks would have been if one of the two aforementioned teams traded their pick to another team (as the Indiana Pacers had done with what eventually became the number-two pick in the previous year's draft).

Beginning with the 1985 draft, the NBA handled matters differently. Every team that qualified for the playoffs received positions based on their winning percentage, and the teams that did not were placed in a lottery. In the first lottery, the NBA did not determine the positions as they do now. In this case, the seven teams that did not qualify for the playoffs were each given an equal chance to get the top pick. Each team had its name and logo put in an envelope, and the envelopes were placed into a hopper and spun to shuffle them. Once done, Commissioner David Stern then drew an envelope from inside to determine who would pick first. In a move that would create controversy for years to come, the envelope Stern drew was the one belonging to the New York Knicks, inviting allegations the draw was rigged;[18][19][20] Stern had also grown up a Knicks fan.[21] The Knicks drafted Ewing, as expected, beginning a 15-year relationship. They then signed him to a 10-year, $32 million contract, a contract that The New York Times years later described as "a tremendous contract at that time or any time."[22]

Although injuries marred his first year in the league, he was voted NBA Rookie of the Year and named to the NBA All-Rookie First Team after averaging 20 points, 9 rebounds, and 2 blocks per game. Soon after he was considered one of the premier centers in the league. Ewing enjoyed a successful career; eleven times named an NBA All-Star, once named to the All-NBA First Team, six times a member of the All-NBA Second Team, and named to the NBA All-Defensive Second Team three times. He was a member of the original Dream Team at the 1992 Olympic Games. He was also given the honor of being named one of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History.

In the 1992 Eastern Conference Semifinals, the Knicks played the defending NBA champion Chicago Bulls and Michael Jordan. Ewing was unstoppable in Game 1, finishing with 34 points, 16 rebounds, and 6 blocks, and the Knicks beat Chicago 94–89. The Knicks were facing elimination in Game 6 when Ewing had one of the greatest games of his career. The team trailed 3–2 in the series, and Ewing was limited physically by a bad ankle sprain,[23] but he helped the Knicks beat the Bulls 100–86 by scoring 27 points. NBC announcer Marv Albert called it a "Willis Reed-type performance", but the Knicks were ultimately eliminated in Game 7 in a blowout, 110–81.

In an April 14, 1993, game,[24] between the Knicks and the Charlotte Hornets, the 7 ft 0 in (2.13 m) Ewing suffered a moment of embarrassment when Muggsy Bogues, a 5-foot-3-inch-tall (1.60 m) point guard for the Hornets, managed to knock the ball loose as Ewing was shooting.[25] The team looked like it was going to advance to the NBA Finals when they took a 2–0 lead over Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls. Both teams battled well, each winning on its home court in the first 4 games. However, the Bulls stunned the Ewing-led Knicks, winning Game 5 in New York 97–94 after Ewing's teammate, Charles Smith, was repeatedly blocked down low by Bulls defenders on the game's final possession. The Bulls would go on to win Game 6 96–88 and then claim their third straight NBA title. This would be one more season in which Ewing had to deal with no championships, despite the fact that the Knicks had the best regular-season record in the Eastern Conference at 60–22 and had the second-best record in the NBA, behind the Phoenix Suns, who were 62–20.

With Jordan out of the league, 1993–94 was considered a wide-open year in the NBA, and Ewing had declared that 1994 would be the Knicks' year. He was a main contributor to the Knicks' run to the 1994 NBA Finals, in which the Knicks—in the Finals for the first time since 1973—lost in the final seconds of Games 6 and 7 to Hakeem Olajuwon's Houston Rockets. The Knicks, with Ewing leading them, had to survive a grueling trek through the playoffs simply to reach the Finals. They defeated the Bulls and Scottie Pippen in seven games in the 1994 Eastern Conference Semifinals (all seven games were won by the home team), and defeated Reggie Miller's Indiana Pacers in the Conference Finals, which also took seven games to decide. In the Finals, the Knicks stole Game 2 in Houston, but could not hold court at home, dropping Game 3 at the Garden. The Knicks then won the next two games to return to Houston ahead 3–2. However, the Rockets won the next two games. Ewing made the most of his playoff run by setting a record for most blocked shots in a Finals series with 30 (later broken by Tim Duncan in 2003 with 32). He also set an NBA Finals record for most blocked shots in a single game, with 8 (surpassed by Dwight Howard in 2009).

The following year, a potential game-tying finger roll by Ewing rimmed out in the dwindling seconds of Game 7 of the Eastern Conference Semifinals, resulting in a loss to the Indiana Pacers. In the 1995–96 season, Ewing and the Knicks were eliminated in the Eastern Conference Semifinals in five games by the record-setting 1995–96 Bulls, who won 72 games that year en route to their fourth championship.

In the 1997 playoffs, the Knicks faced the Miami Heat in the Eastern Conference Semifinals. Ewing was involved in a Game 5 brawl where both teams' benches got involved. The Knicks, who were up 3–1 in the series going into Game 5, lost the next three games and were eliminated.

In the next season, Ewing's career almost came to an end due to an injury. On December 20, 1997, in a game against the Milwaukee Bucks at the Bradley Center, Ewing was fouled by Andrew Lang while attempting a dunk.[26] Ewing fell awkwardly and landed with all of his weight on his shooting hand. The result was a severely damaged wrist, with Ewing suffering a displaced fracture, a complete dislocation of the lunate bone, and torn ligaments. These injuries required emergency surgery to prevent nerve damage, and it was said that Ewing suffered injuries that were usually reserved for victims of vehicular accidents.[27]

Ewing, who had only missed 20 games in the previous ten seasons, missed the remaining 56 games of the season,[28] but he was able to rehabilitate the injury faster than expected, and as the playoffs began Ewing was talking about returning. The Heat and Knicks met in the playoffs for the second straight year. This time, the two teams met up in the first round of the playoffs. The series went to a decisive fifth game, but the Knicks avenged their loss to Miami the year before by beating the Heat in Miami 98–81. Ewing returned for Game 2 of the Eastern Conference Semifinals against the Pacers. His presence was not enough, however, as the Knicks fell to the Pacers in five games.

The following season, Ewing and the Knicks qualified as the East's eighth seed in a lockout-shortened season. Although battling an achilles tendon injury, Ewing led the Knicks to another victory over the Heat in the first round, 3–2. In the series-clinching Game 5, he scored 22 points and grabbed 11 rebounds.[29] They followed that up by sweeping the Atlanta Hawks, and defeated the Pacers in the Conference Finals in 6 games, despite Ewing's injury finally forcing him out of action. The Knicks could not, however, complete their Cinderella run, as they lost in the Finals to the San Antonio Spurs, 4–1.

In Ewing's final season with the Knicks in 1999–2000, the team finished as the third seed in the East behind the Pacers and Heat. The team advanced to the Conference Finals again, sweeping the Toronto Raptors and beating the Heat for the third straight year in seven games, but could not defeat the Pacers and fell in six games. In his last year with the Knicks, Ewing had a game-winning slam dunk over Alonzo Mourning in Game 7 of the Eastern Conference Semifinals to lead the Knicks to the Eastern Conference Finals. During his final season with the Knicks, Ewing played in his 1,000th NBA game, finishing his Knick career with a franchise-record 1,039 games played in a Knick uniform (he is the only player to play 1,000 games with the Knicks).

Post-Knicks career

[edit]During the 2000 off-season, Ewing requested a trade from New York, and the Knicks complied, sending Ewing to the Seattle SuperSonics in a four-team trade; the Knicks also sent Chris Dudley to Phoenix in the deal, and received Glen Rice, Luc Longley, Travis Knight, Vladimir Stepania, Lazaro Borrell, Vernon Maxwell, two first-round draft picks (from the Los Angeles Lakers and Seattle) and two second-round draft picks from Seattle.[30] After one season with the SuperSonics and another with the Orlando Magic, he announced his retirement on September 18, 2002. After that season, he took a job as an assistant coach with the Washington Wizards.

In 1,183 games over 17 seasons, Ewing averaged 21.0 points, 9.8 rebounds, and 2.4 blocks per game, and averaged better than a 50% shooting percentage. As of 2021, Ewing was ranked 23rd on the NBA scoring list with 24,815 points.[31]

Ewing played 1,039 games for the Knicks. On February 28, 2003, his jersey number 33 was retired by the team in a large ceremony at Madison Square Garden.

For the first time ever, Ewing represented the Knicks during the NBA draft lottery on May 14, 2019.[32] They got the third overall pick in the 2019 NBA draft.[33]

In October 2024, it was announced that Ewing would rejoin the Knicks as a basketball ambassador.[34]

National team career

[edit]Ewing won Olympic gold medals as a member of the 1984 and 1992 United States men's basketball teams.[4] In 1984, Ewing averaged 11.0 points in eight games, and was the tournament's leading shot blocker with 18.[35][36] The Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame referred to the 1992 "Dream Team" as "the greatest collection of basketball talent on the planet".[37]

Awards and honors

[edit]

- Rookie of the Year (1986)

- All-NBA First Team (1990)

- All-NBA Second Team (1988, 1989, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1997)

- NBA All-Defensive Second Team (1988, 1989, 1992)

- 11-time All-Star; One of 50 Greatest Players in NBA History (1996)

- 2-time Olympic gold medalist (1984, 1992)

- 3-time All-American (1983–1985)

- NCAA basketball tournament Most Outstanding Player (1984)

- Naismith College Player of the Year (1985).

- AP College Player of the Year (1985)

- NABC Player of the Year (1985)

- Sporting News College Player of the Year (1985)

- Adolph Rupp Trophy (1985)

- No. 33 retired for the New York Knicks

- Basketball Hall of Fame inductee (in 2008 as an individual and 2010 as a member of the Dream Team)

- NBA 75th Anniversary Team (2021)

Ewing was a defensive stalwart throughout his basketball career, although he often had difficulty placing on the NBA All-Defensive Team due to the defensive prowess of his contemporaries Hakeem Olajuwon and David Robinson.

In 1993, he led the NBA with 789 defensive rebounds. He was top ten in field goal percentage eight times, top ten in rebounds per game and total rebounds eight times, top ten in points and points per game eight times, and top ten in blocks per game for 13 years.[39]

In 1999, Ewing became the 10th player in NBA history to record 22,000 points and 10,000 rebounds.

NBA career statistics

[edit]| GP | Games played | GS | Games started | MPG | Minutes per game |

| FG% | Field goal percentage | 3P% | 3-point field goal percentage | FT% | Free throw percentage |

| RPG | Rebounds per game | APG | Assists per game | SPG | Steals per game |

| BPG | Blocks per game | PPG | Points per game | Bold | Career high |

Regular season

[edit]| Year | Team | GP | GS | MPG | FG% | 3P% | FT% | RPG | APG | SPG | BPG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1985–86 | New York | 50 | 50 | 35.4 | .474 | .000 | .739 | 9.0 | 2.0 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 20.0 |

| 1986–87 | New York | 63 | 63 | 35.0 | .503 | .000 | .713 | 8.8 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 21.5 |

| 1987–88 | New York | 82 | 82 | 31.0 | .555 | .000 | .716 | 8.2 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 3.0 | 20.2 |

| 1988–89 | New York | 80 | 80 | 36.2 | .567 | .000 | .746 | 9.3 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 3.5 | 22.7 |

| 1989–90 | New York | 82 | 82 | 38.6 | .551 | .250 | .775 | 10.9 | 2.2 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 28.6 |

| 1990–91 | New York | 81 | 81 | 38.3 | .514 | .000 | .745 | 11.2 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 3.2 | 26.6 |

| 1991–92 | New York | 82 | 82 | 38.4 | .522 | .167 | .738 | 11.2 | 1.9 | 1.1 | 3.0 | 24.0 |

| 1992–93 | New York | 81 | 81 | 37.1 | .503 | .143 | .719 | 12.1 | 1.9 | .9 | 2.0 | 24.2 |

| 1993–94 | New York | 79 | 79 | 37.6 | .496 | .286 | .765 | 11.2 | 2.3 | 1.1 | 2.7 | 24.5 |

| 1994–95 | New York | 79 | 79 | 37.0 | .503 | .286 | .750 | 11.0 | 2.7 | .9 | 2.0 | 23.9 |

| 1995–96 | New York | 76 | 76 | 36.6 | .466 | .143 | .761 | 10.6 | 2.1 | .9 | 2.4 | 22.5 |

| 1996–97 | New York | 78 | 78 | 37.0 | .488 | .222 | .754 | 10.7 | 2.0 | .9 | 2.4 | 22.4 |

| 1997–98 | New York | 26 | 26 | 32.6 | .504 | .000 | .720 | 10.2 | 1.1 | .6 | 2.2 | 20.8 |

| 1998–99 | New York | 38 | 38 | 34.2 | .435 | .000 | .706 | 9.9 | 1.1 | .8 | 2.6 | 17.3 |

| 1999–00 | New York | 62 | 62 | 32.8 | .435 | .000 | .731 | 9.7 | .9 | .6 | 1.4 | 15.0 |

| 2000–01 | Seattle | 79 | 79 | 26.7 | .430 | .000 | .685 | 7.4 | 1.2 | .7 | 1.2 | 9.6 |

| 2001–02 | Orlando | 65 | 4 | 13.9 | .444 | .000 | .701 | 4.0 | .5 | .3 | .7 | 6.0 |

| Career | 1,183 | 1,122 | 34.3 | .504 | .152 | .740 | 9.8 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 21.0 | |

| All-Star | 9 | 3 | 17.8 | .537 | .000 | .692 | 6.7 | .8 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 11.8 | |

Playoffs

[edit]| Year | Team | GP | GS | MPG | FG% | 3P% | FT% | RPG | APG | SPG | BPG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1988 | New York | 4 | 4 | 38.3 | .491 | .000 | .864 | 12.8 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 3.3 | 18.8 |

| 1989 | New York | 9 | 9 | 37.8 | .486 | — | .750 | 10.0 | 2.2 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 19.9 |

| 1990 | New York | 10 | 10 | 39.5 | .521 | .500 | .823 | 10.5 | 3.1 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 29.4 |

| 1991 | New York | 3 | 3 | 36.7 | .400 | — | .778 | 10.0 | 2.0 | .3 | 1.7 | 16.7 |

| 1992 | New York | 12 | 12 | 40.2 | .456 | .000 | .740 | 11.1 | 2.3 | .6 | 2.6 | 22.7 |

| 1993 | New York | 15 | 15 | 40.3 | .512 | 1.000 | .638 | 10.9 | 2.4 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 25.5 |

| 1994 | New York | 25 | 25 | 41.3 | .437 | .364 | .740 | 11.7 | 2.6 | 1.3 | 3.0 | 21.9 |

| 1995 | New York | 11 | 11 | 36.3 | .513 | .333 | .686 | 9.6 | 2.5 | .5 | 2.3 | 19.0 |

| 1996 | New York | 8 | 8 | 41.0 | .474 | .500 | .651 | 10.6 | 1.9 | .1 | 3.1 | 21.5 |

| 1997 | New York | 9 | 9 | 39.7 | .527 | .000 | .643 | 10.6 | 1.9 | .3 | 2.4 | 22.6 |

| 1998 | New York | 4 | 4 | 33.0 | .357 | — | .593 | 8.0 | 1.3 | .8 | 1.3 | 14.0 |

| 1999 | New York | 10 | 10 | 31.5 | .430 | — | .593 | 8.7 | .5 | .6 | .7 | 13.1 |

| 2000 | New York | 14 | 14 | 32.9 | .418 | — | .697 | 9.5 | .4 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 14.6 |

| 2002 | Orlando | 4 | 0 | 16.8 | .320 | .000 | .588 | 5.5 | 1.0 | .3 | 1.0 | 6.5 |

| Career | 139 | 135 | 37.5 | .469 | .348 | .718 | 10.3 | 2.0 | .9 | 2.2 | 20.2 | |

Coaching career

[edit]From 2002 to 2003, Ewing served as an assistant coach for the Washington Wizards under the ownership of his longtime rival Michael Jordan. From 2003 through 2006, Ewing was an assistant with the Houston Rockets, before resigning to spend more time with his family. On July 3, 2007, Ewing was one of four assistants hired to serve under first-year Orlando Magic head coach Stan Van Gundy[40] for the 2007–08 season.

The Magic reached the 2009 NBA Finals, where they lost to the Los Angeles Lakers. He correctly predicted a win in Game 7 of the second round against the defending champion Boston Celtics.[41] Later in the playoffs, Ewing saw Magic captain Dwight Howard set a new NBA Finals record for most blocked shots in a single Finals game, with nine in Game 4, surpassing the previous record of eight by Ewing himself in Game 5 of the 1994 Finals.

In 2010, Ewing finally got the opportunity to coach his son Patrick Ewing Jr. in the 2010 summer league. Ewing Jr. played for the Magic.[42]

In 2013, Ewing became an assistant coach with the Charlotte Bobcats (now Charlotte Hornets).[43] On November 8, 2013, Ewing became the Bobcats' interim head coach due to regular head coach Steve Clifford having heart surgery. He lost his first game 101–91 against his former team, the Knicks.

On April 3, 2017, Ewing was hired as head coach of his former college team, the Georgetown Hoyas.[44] In his first season as head coach, the Hoyas were 15–15 (5–13 in the Big East). The season ended without any postseason tournament play. In Ewing's second season, Georgetown was 19–14, and finished tied in third place in the Big East with a 9–9 record. The Hoyas were awarded a bid in the 2019 National Invitation Tournament, their first postseason tournament since 2015. James Akinjo was named the Big East Rookie of the Year, and fellow freshmen Mac McClung and Josh Leblanc joined him on the Big East All-Freshman Team. In Ewing's third season, the Hoyas finished 15–17 overall and 5–13 in the Big East and lost in the first round of the 2020 Big East tournament the day before all further postseason play was cancelled due to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In Ewing's fourth season, after finishing the regular season with a record of 13–13 overall and 7–9 in the Big East, he led the Hoyas to the 2021 Big East Conference tournament championship as the eighth seed in the tournament.[45] They defeated the first-seeded Villanova Wildcats in the quarterfinals.[46] In the championship game, Georgetown defeated the second-seeded Creighton Bluejays 73–48, and qualified for the 2021 NCAA Division I basketball tournament.[47] This marked Georgetown's first NCAA tournament appearance since the 2014–15 season, breaking their longest NCAA drought in the modern era. The Hoyas were unable to build on this success in Ewing's fifth season however, posting an overall record of 6–25 and going winless in Big East Conference play at 0–19 in the regular season followed by a first-round loss in the 2022 Big East tournament. In Ewing's sixth season, Georgetown finished with an overall record of 7–25 and 2–18 in the Big East, including a first-round exit from the 2023 Big East tournament. On March 9, 2023, Ewing was fired as coach.[48]

Head coaching record

[edit]| Season | Team | Overall | Conference | Standing | Postseason | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Georgetown Hoyas (Big East Conference) (2017–2023) | |||||||||

| 2017–18 | Georgetown | 15–15 | 5–13 | 8th | |||||

| 2018–19 | Georgetown | 19–14 | 9–9 | T–3rd | NIT First Round | ||||

| 2019–20 | Georgetown | 15–17 | 5–13 | T–8th | |||||

| 2020–21 | Georgetown | 13–13 | 7–9 | 8th | NCAA Division I Round of 64 | ||||

| 2021–22 | Georgetown | 6–25 | 0–19 | 11th | |||||

| 2022–23 | Georgetown | 7–25 | 2–18 | 11th | |||||

| Georgetown: | 75–109 (.408) | 28–81 (.257) | |||||||

| Total: | 75–109 (.408) | ||||||||

|

National champion

Postseason invitational champion

| |||||||||

Other work

[edit]Ewing interned in the office of Senator Bob Dole during multiple summers in college.[49][50]

Ewing was in the 1996 movie Space Jam as himself, one of five NBA players whose talent was stolen (along with Charles Barkley, Shawn Bradley, Larry Johnson, and Muggsy Bogues). Ewing had a brief appearance, again as himself, in the movie Senseless starring Marlon Wayans.

Ewing made cameos as himself in the sitcoms Spin City, Herman's Head, Mad About You, and Webster.[51] Most recently, he appeared in a 2009 ad for Snickers, suggesting that those who eat the candy bar might "get dunked on by Patrick Chewing". He also made a silent cameo as the Angel of Death in The Exorcist III.

He co-wrote In the Paint, a painting how-to book for children.[52]

In 2014, Ewing and sports agent David Falk announced a $3.3 million donation to the John R. Thompson, Jr. Intercollegiate Athletics Center under construction at Georgetown University. The amount is a reference to Ewing's number, 33.[53]

Endorsements

[edit]Ewing's first sneaker endorsement was with Adidas in 1986.[54] In 1991, Next Sports signed a licensing deal to release footwear under Ewing's name in the United States under a new company, Ewing Athletics, which would operate until 1996.[55] In 2012, David Goldberg and his company GPF Footwear LLC successfully teamed up with Ewing to resurrect the old Ewing Athletics line, and bring it back into stores, capitalizing on the current retro trend in the footwear market.[56]

Personal life

[edit]

Ewing was married to Rita Williams from 1990 to 1998.[57] He has three children, including Patrick Ewing Jr.[58][59]

In July 2001, Ewing testified in the federal trial of an Atlanta club owner charged with facilitating prostitution. Ewing told the court he received oral sex from dancers at the club in 1996 and 1997, but did not pay any money for the encounters and did not feel that he was involved in an act of prostitution.[60][61][62][63][64] Ewing was never charged with a crime in connection with The Gold Club encounters.[65]

After friend and rival NBA center Alonzo Mourning was diagnosed with a kidney ailment in 2000, Ewing promised that he would donate one of his kidneys to Mourning if he ever needed one.[66] In 2003, Ewing was tested for kidney compatibility with Mourning, but Mourning's cousin was found to be the better match.[67]

Patrick Ewing Jr. transferred to his father's alma mater, Georgetown University, after two years at Indiana University. Patrick Jr. wore the same jersey number that his father wore, #33. He was drafted by the Sacramento Kings in the second round with the 43rd pick of the 2008 NBA draft, but was then traded to the New York Knicks, his father's old team.

See also

[edit]- Georgetown Hoyas men's basketball

- List of NBA career scoring leaders

- List of NBA franchise career scoring leaders

- List of NBA career rebounding leaders

- List of NBA career blocks leaders

- List of NBA career turnovers leaders

- List of NBA career personal fouls leaders

- List of NBA career free throw scoring leaders

- List of NBA career minutes played leaders

- List of NBA career playoff rebounding leaders

- List of NBA career playoff blocks leaders

- List of NCAA Division I men's basketball players with 2,000 points and 1,000 rebounds

References

[edit]- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Patrick Ewing's number retired at MSG". NBA. March 26, 2011. Retrieved July 17, 2016 – via YouTube.

- ^ African Americans in Sports. Routledge. March 26, 2015. ISBN 9781317477433. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ "25 Greatest Players In College Basketball". ESPN.com. March 8, 2008. Archived from the original on April 23, 2022. Retrieved January 30, 2014.

- ^ a b "Patrick Ewing Bio". NBA.com. NBA. February 8, 2015. Archived from the original on February 21, 2007. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

- ^ "NBA's 75 Anniversary Team Players | NBA.com | NBA.com". www.nba.com. Archived from the original on February 17, 2022. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ^ "50 Greatest Players in NBA History". Basketball Reference. February 8, 2015. Archived from the original on September 3, 2022. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

- ^ ay. "The Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame – Hall of Famers". Hoophall.com. Archived from the original on August 18, 2010. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

- ^ Latino and African American Athletes Today: A Biographical Dictionary. Greenwood Publishing. 2004. ISBN 9780313320484. Archived from the original on February 10, 2024. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ Wise, Mike (March 13, 2008). "Ewing Gives Hoyas a Little Pop". Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 9, 2018. Retrieved September 7, 2017.

- ^ Bunn, Curtis (September 11, 1994). "Journey Recalls Racism For Ewing – South Africa Trip Eye-Opener For Knicks Star". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on March 14, 2013. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- ^ Common Enemies: Georgetown Basketball, Miami Football, and the Racial Transformation of College Sports. U of Nebraska Press. November 2021. ISBN 9781496230041. Archived from the original on April 20, 2023. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ Norlander, Matt (June 13, 2013). "Patrick Ewing says KKK 'rally' partly why he didn't attend UNC". CBS Sports. Archived from the original on August 26, 2014. Retrieved August 21, 2014.

- ^ "When Patrick Ewing Committed to Georgetown | 30 for 30 | ESPN Stories - YouTube". YouTube. Archived from the original on April 18, 2022. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ "Georgetown Basketball History: The Top 100". hoyabasketball.com. Archived from the original on July 23, 2018. Retrieved January 10, 2020.

- ^ "The Georgetown Basketball History Project: Classic Games". Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "Kentucky vs. Georgetown (March 31, 1984)". www.bigbluehistory.net. Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved January 10, 2020.

- ^ "Links while tossing around conspiracy theories". ESPN.com. April 19, 2007. Archived from the original on October 6, 2019. Retrieved January 30, 2014.

- ^ "The Ewing Conspiracy". Sports Illustrated Longform. Archived from the original on March 15, 2023. Retrieved December 11, 2022.

- ^ "TSN Originals: David Stern, the Knicks, Patrick Ewing and the 1985 NBA Draft Lottery conspiracy theories". www.sportingnews.com. May 17, 2022. Archived from the original on June 25, 2022. Retrieved June 25, 2022.

- ^ Levitt, Daniel (December 7, 2022). "Fifty Years After Their Last NBA Title, The Knicks Are Still Adrift". FiveThirtyEight. Archived from the original on December 11, 2022. Retrieved December 11, 2022.

- ^ "NBA Commissioner Emeritus David Stern dies at 77". www.nba.com. Archived from the original on June 25, 2022. Retrieved June 25, 2022.

- ^ Berkow, Ira (August 4, 1991). "Sports of the Times; What Is Next Move For Patrick Ewing?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- ^ Brown, Clifton (May 17, 1992). "BASKETBALL; Ewing Feels Good Enough". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved September 6, 2009.

- ^ "New York Knicks at Charlotte Hornets Box Score, April 14, 1993". Basketball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on October 13, 2019. Retrieved January 10, 2020.

- ^ Stoelting, Suzanne (October 4, 1996). "@Herald: The agony of short people". yaleherald.com. Archived from the original on September 22, 2006. Retrieved January 30, 2014.

- ^ "Ewing Goes Down, so Do the Knicks". Los Angeles Times. December 21, 1997. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved January 10, 2020.

- ^ Roberts, Selena (December 22, 1997). "PRO BASKETBALL – Wrist Surgery Sidelines Ewing For the Season". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

- ^ "New York Knicks' Patrick Ewing out for season after two-hour surgery following wrist injury". Jet. 1998. Archived from the original on June 28, 2010. Retrieved July 8, 2010.

- ^ "New York Knicks at Miami Heat Box Score, May 16, 1999". Basketball Reference. Archived from the original on June 29, 2021. Retrieved August 11, 2021.

- ^ Sheridan, Chris (September 21, 2000). "THE NBA: Ewing finally a Sonic". Archived from the original on August 6, 2023. Retrieved August 6, 2023.

- ^ "NBA & ABA Career Leaders and Records for Points". Basketball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on February 25, 2011. Retrieved March 19, 2021.

- ^ "Ewing headlines team participants for 2019 NBA Draft Lottery". NBA.com. May 8, 2019. Archived from the original on May 12, 2019. Retrieved January 10, 2020.

- ^ "Pelicans win NBA Draft Lottery". NBA.com. May 14, 2019. Archived from the original on January 24, 2020. Retrieved January 10, 2020.

- ^ "Ewing rejoins Knicks as basketball ambassador". ESPN.com. October 4, 2024. Retrieved October 4, 2024.

- ^ [1] Archived November 26, 2022, at the Wayback MachineBasketball Reference

- ^ "Games of the XXIIIrd Olympiad -- 1984". USA Basketball. Archived from the original on April 29, 2015. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ^ "The Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame - Hall of Famers". August 18, 2010. Archived from the original on August 18, 2010. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ^ "Patrick Ewing Selected to Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame". Georgetown University Athletics. April 7, 2008. Archived from the original on June 6, 2015. Retrieved June 28, 2011.

- ^ "Patrick Ewing Stats". Basketball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved January 30, 2014.

- ^ "Ewing, Malone, Clifford, Beyer hired as Magic coaches". ESPN.com. Associated Press. July 3, 2007. Archived from the original on August 27, 2007. Retrieved July 4, 2007.

- ^ Berman, Marc (May 18, 2009). "EWING PROPHETIC AS MAGIC BEAT CELTICS IN GAME 7". New York Post. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ^ Denton, John (July 6, 2010). "Denton: Ewing Finally Gets to Coach Son". NBA.com. Archived from the original on September 22, 2020. Retrieved January 10, 2020.

- ^ "Ewing Meets Media". NBA.com. June 19, 2013. Archived from the original on June 22, 2013. Retrieved January 30, 2014.

- ^ Tracy, Marc (April 3, 2017). "Georgetown Hires Patrick Ewing as Men's Basketball Coach". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 2, 2017. Retrieved April 4, 2017.

- ^ Salvador, Joseph (March 13, 2021). "Patrick Ewing-Led Georgetown Completes Big East Run to Steal NCAA Tournament Bid". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on March 14, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ "Georgetown upsets Big East top-seeded Villanova 72-71 at MSG". ESPN.com. March 11, 2021. Archived from the original on March 13, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ "Patrick Ewing-led Georgetown stuns Creighton to win Big East men's basketball title, punch NCAA tournament ticket". ESPN.com. March 13, 2021. Archived from the original on March 14, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ Borzello, Jeff (March 9, 2023). "Patrick Ewing out as Georgetown men's basketball coach". ESPN. Archived from the original on March 9, 2023. Retrieved March 9, 2023.

- ^ Maraniss, David (October 31, 1996). "WITH ROOTS IN THE MIDDLE, DOLE SHIFTED UNEASILY ON A RACIAL ISSUE". Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 5, 2020. Retrieved September 8, 2020.

- ^ Clarity, James F.; Gailey, Phil (June 16, 1983). "Briefing". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 10, 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2020.

- ^ "Patrick Ewing". IMDb. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved January 10, 2020.

- ^ Ewing, Patrick Aloysius; Louis, Linda L. (April 1, 1999). In the Paint: Patrick Ewing, Linda L. Louis: 9780789205421. Abbeville Kids. ISBN 0789205424.

- ^ Wang, Gene (August 25, 2014). "Patrick Ewing, David Falk donate $3.3 million toward Georgetown facility". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

- ^ Halfhill, Matt (May 8, 2008). "Throwback Thursday – Original Adidas Attitude Ewing". Nice Kicks. Archived from the original on April 12, 2018. Retrieved January 30, 2014.

- ^ Lee, Sharon (February 11, 1991). "Next Sports receives Ewing rights in U.S." Footwear News. Archived from the original on June 11, 2014. Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- ^ Rovell, Darren (August 28, 2012). "Ewing Athletics relaunching". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on November 28, 2016. Retrieved January 30, 2014.

- ^ Aby Rivas (June 1, 2020). "Patrick Ewing Is a Proud Dad of Three Grown-Up Kids — Meet the NBA Legend's Family". amomama.com. Archived from the original on June 3, 2020. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ Neil Milbert (January 26, 2004). "Ewing Jr. is still a work in progress". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on June 3, 2020. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- ^ Chris Bucher (April 3, 2017). "Patrick Ewing's Family: 5 Fast Facts You Need to Know". Heavy.com. Archived from the original on June 3, 2020. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ Guart, Al (July 24, 2001). "Pat Gives Oral Sex Testimony". New York Post. Archived from the original on January 27, 2023. Retrieved January 27, 2023.

- ^ "NBA Star Got Sexual Favors". cbsnews.com. July 23, 2001. Archived from the original on August 19, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ^ Firestone, David (July 24, 2001). "In Testimony, Patrick Ewing Tells of Favors At Strip Club". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 19, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ^ "NBA Star Ewing Testifies in Strip Club Trial". ABC News. July 23, 2001. Archived from the original on August 19, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ^ "Ewing testifies he twice had oral sex at Gold Club". ESPN. July 24, 2001. Archived from the original on August 19, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ^ "NBA star Ewing testifies at strip club trial". CNN. July 24, 2001. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ "Patrick Ewing Offers Kidney To Ailing Friend Alonzo Mourning". Jet. 2000. Archived from the original on June 23, 2006.

- ^ Lopresti, Mike (June 10, 2006). "Donating kidney 'a no-brainer' for Mourning's cousin". USA Today. Archived from the original on January 10, 2012. Retrieved September 7, 2017.

External links

[edit]- Career statistics from NBA.com and Basketball Reference

- Patrick Ewing at the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame

- Patrick Ewing entry at NBA Encyclopedia

- Season-by-season notes (1985–2000)

- 1962 births

- Living people

- All-American college men's basketball players

- American men's basketball coaches

- American men's basketball players

- Basketball coaches from Massachusetts

- Basketball players at the 1984 Summer Olympics

- Basketball players at the 1992 Summer Olympics

- Cambridge Rindge and Latin School alumni

- Centers (basketball)

- Charlotte Bobcats assistant coaches

- Charlotte Hornets assistant coaches

- Georgetown Hoyas men's basketball coaches

- Georgetown Hoyas men's basketball players

- Houston Rockets assistant coaches

- Jamaican emigrants to the United States

- Jamaican men's basketball players

- McDonald's High School All-Americans

- Medalists at the 1984 Summer Olympics

- Medalists at the 1992 Summer Olympics

- Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame inductees

- NBA All-Stars

- NBA players from Jamaica

- NBA players with retired numbers

- National Basketball Players Association presidents

- National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame inductees

- New York Knicks draft picks

- New York Knicks players

- Olympic gold medalists for the United States in basketball

- Orlando Magic assistant coaches

- Orlando Magic players

- Parade High School All-Americans (boys' basketball)

- Naturalized citizens of the United States

- Seattle SuperSonics players

- Sportspeople from Cambridge, Massachusetts

- Basketball players from Middlesex County, Massachusetts

- Basketball players from Kingston, Jamaica

- United States men's national basketball team players

- Washington Wizards assistant coaches

- First overall NBA draft picks

- Naturalised basketball players